Along the same saccharine lines as Annie's character, the daughters are often shot in soft focus as they literally cling to their parents for their precious lives.

Whatever seeds of social justice and emotional nuance No Escape may be attempting to sow are undercut by the film's melodramatic valorization of family values. Just then, Annie lifts her heavy eyes and levels with him matter of factly: "I can't comfort you right now." Unfortunately, the brief insight Annie has into her husband's consuming ego dwindles throughout the film as her role as damsel in distress gains momentum. In his self-absorption, Jack can't help but whine about how hard the move has been for him and of his fears of letting down the family. During their first night in the hotel Jack finds Annie crying in the bathroom, homesick and overwhelmed. Annie shifts from a dynamic character – she is gentle but somewhat critical of her putz of a husband – to a woman whose most profound achievement and raison d'être is being a mother and wife. Lake Bell deserves better than No Escape. Consumerist desire is indulged, but the guilt it produces is placated by the Toms fantasy of goodwill and generosity. Annie's choice of footwear is the perfect marriage of capitalism and Western charity: When you buy a pair of these flimsy shoes, another pair is given to a poor kid somewhere. They are shod in the grey canvas of Toms shoes and featured prominently as she leaps and bounds through the film, narrowly escaping repeated assaults by the rebels. Take Jack, who thinks his new job is about bringing clean drinking water to millions, when, in fact, he learns (from a scruffy, whisky-drinking Pierce Brosnan) that the company is simply draining the natural resources of an impoverished country. No Escape has a funny relationship to charity and to the ethical stakes of large corporations doing business in developing nations. Walking through the foreign streets in his basic-bro, blue button-down shirt and khaki pants, it's as though he is reprising his role as hapless flâneur in Woody Allen's Midnight in Paris, but this time with an appetite for American altruism. He passes a small drum circle, drops a few dollars at the players' feet (good guy that he is), and continues to meander through market streets, admiring wind chimes and the like. The morning after the Dwyer family's arrival, Jack goes out looking for a newspaper and wanders through the streets in a charmed daze. The film's opening sequence is the most appealing thanks to Wilson's ability to perform obliviousness better than any other actor I can think to name (it seems he always plays a version of Eli Cash, the coked-out, heart-of-gold cowboy from The Royal Tenenbaums). The film opens with the violent military coup – we see an unnamed head of state assassinated by a motley rebel army – but Jack and his family are oblivious as they descend into the terror from 39,000 feet. Tail between his legs, he finds himself on a plane heading to Southeast Asia to start again by working for a multinational corporation with his two apple-cheeked little girls and supportive wife, Annie (Lake Bell), in tow.

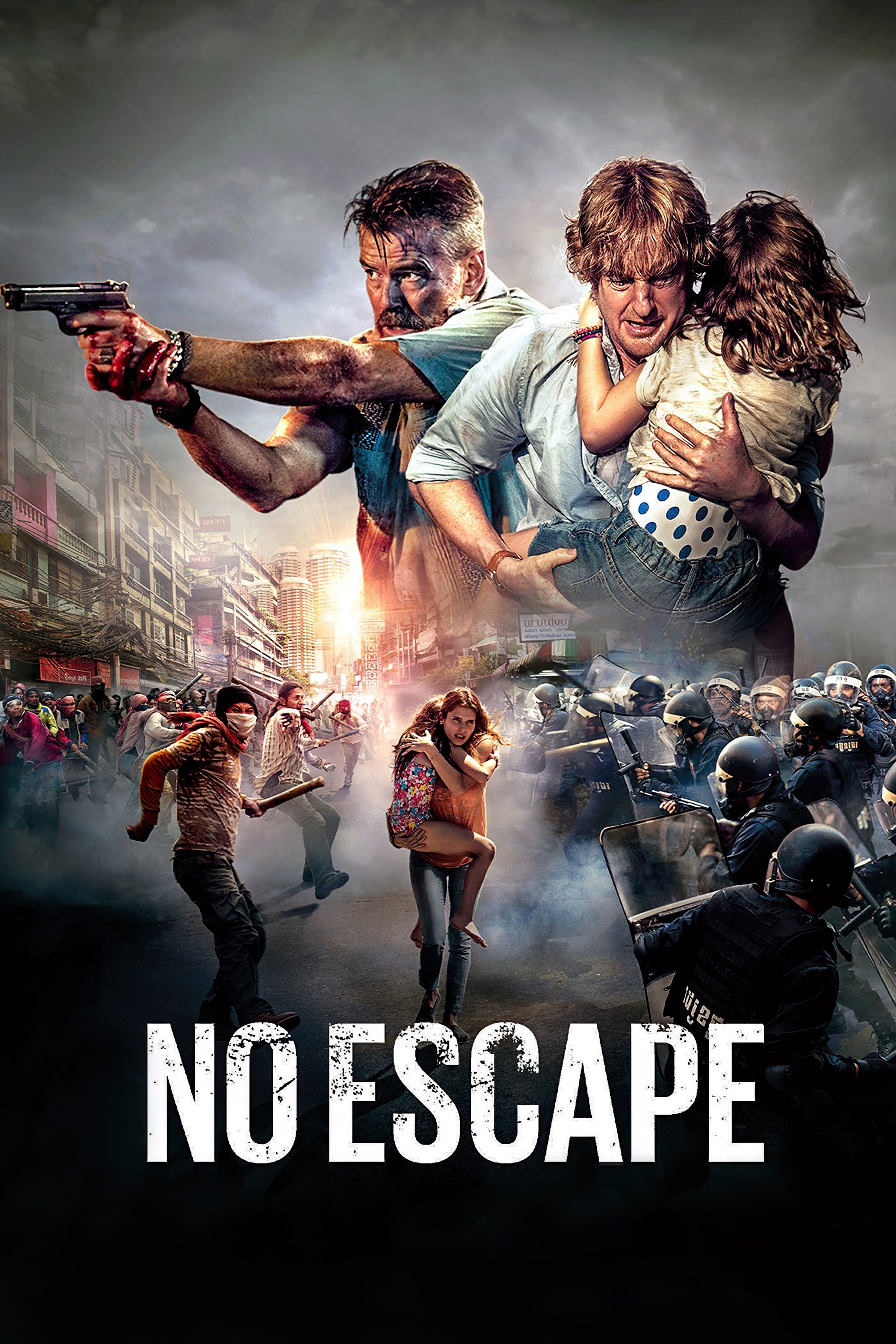

Wilson plays Jack Dwyer, an engineer whose attempt at entrepreneurship back home in Texas has flopped. Oddly, it stars renowned nice guy Owen Wilson, whose gee-shucks demeanour feels at odds with the action-packed, gun-slinging genre. Filmed in northern Thailand, director John Erick Dowdle's No Escape is a coup d'état family suspense thriller with a First World guilt complex.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)